5 years on from the COVID-induced shift to mass online learning – where are we now in the Australian tertiary education sector?

In early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept the globe, Australia’s higher education and VET providers were forced to pivot almost overnight to fully online learning. What began as a stop-gap emergency response to a major public health crisis has since morphed into a long-term transformation of the post-secondary education landscape.

Initially institutions scrambled to digitise content, teachers learned to teach through Zoom, and students adapted to new modes of learning and assessment. While there was an initial and understandable willingness to accept a less engaging learning experience – as the price for this rapid shift, there was also optimism that this shift could accelerate innovation and (in some instances) improve access to high quality education.

Five years on the question is whether the promises of digital transformation have been realised—or if, instead, we have succumbed to the “regressive triumph of the lowest tech”?[1]

As the sector grapples with projections that 90% of all future jobs will require either a VET or higher education qualification,[2] and after two years focussed on the academic integrity risks of generative AI (GenAI), serious concerns remain about the pedagogical quality of online education, the social and academic isolation experienced by many students, and the financial sustainability of EdTech providers that once seemed poised to revolutionise learning.

Has online learning lived up to its potential—or are we still stuck in the “Zoom and PowerPoint” phase of digital education and if so, how do we move beyond it?

Extent of online learning

In 2023, 47% of students in Australian higher education were either studying externally or ‘multi-modal’.[3] That is their mode of attendance was either:

- External: “where lesson materials, assignments, etc. are delivered to the student, and any associated attendance at the institution is of an incidental, irregular, special or voluntary nature” or

- Multi-modal: where study is undertaken partially on a internal mode (ie through attending the institution on a regular basis or where the student attends on an agreed schedule for the purpose of supervision and/or instruction) and partially on an external mode of attendance.[4]

This categorisation of course only partially accounts for the extent of online learning in higher education, as there are many ‘on campus’ students who have an ‘internal’ mode of attendance but whose lectures have all been moved to online delivery and their on campus attendance relates only to attending tutorials or workshops, etc.

The Australian VET sector uses similar categories to classify student attendance – in this case: internal (eg classroom based), external (eg online), workplace-based, and mixed-mode (ie a combination of these categories). In 2023, across all 32 million subject enrolments, 49% of students were enrolled in VET delivered ‘internally’ and the remainder were in external, workplace, or a mixed combination of delivery modes. That is 51% were not solely attending classes in-person.[5]

So there is a lot of online learning taking place in Australia’s post-school system, even in the “hands on VET sector.”

At the same time, there is evidence that some students are feeling increasingly isolated in their learning experiences.

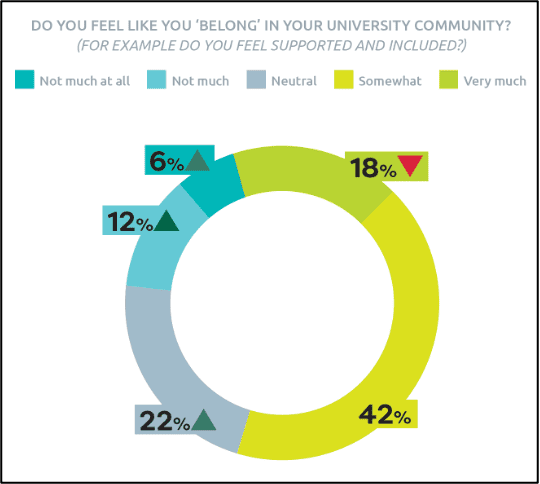

Last year on the What Now? What Next? podcast I spoke with Mike Larsen from Studiosity about their recent survey of more than 1,200 students across Australia’s public universities.[6] The most shocking finding of the research for me was the low levels of connection or belonging for so many students.

Almost half (40%) feel neutral or negative about belonging to their university community:

Digging into the responses – the study reported mixed views about online/mixed modal study. For example:

The comments from the students surveyed by Studiosity, the report’s broader findings and research on the growing mental health issues young people are facing,[7] [8] and reflections like these from academics grappling with asynchronous teaching and GenAI, have been on my mind since recording that podcast episode.

“In a classroom, students and professors engage with one another not just in real time, but in real space—a privileged moment during which we are, well, in sync with one another. The ping-pong of questions and answers, the exchange of interpretations, the spontaneity of reactions, and, if you are lucky, the suddenness of an insight all happen when a group finds itself in sync.

In an asynchronous setting, however, students and instructors are out of sync… Studies reveal that my experience is not unique: learning outcomes in asynchronous classes are persistently lower than in online synchronous or in-person classes. Students perform less well in online courses in general: based on a recent survey at University of California, Irvine, the nonprofit education site The Hechinger Report concluded that students who took online classes graduated more quickly but “tended to get lower grades in their online classes—a sign that they’re learning less than they would have in a traditional class.”

Not surprisingly, more than a few of my students seem to be using artificial intelligence to write their comments. More dismaying, though, is my discovery that AI could as easily teach this class as I can. Apart from the discussion board—the virtual depot for mostly indifferent or impenetrable remarks—these classes offer no possibility of contact or connection between students and teachers. Posting a video is like tossing a message in a bottle into the virtual sea of the internet, wondering if it will reach ever wash onto another shore.”[9]

While the leap may not initially be obvious, these issues have also been at the forefront of my thinking as I have reflected on the fall in valuation last year for three of the leading global EdTech stocks:[10] 2U/edX, Coursera and Keypath Education and the decision to take two of them private (ie to delist 2U/edX from the NASDAQ, and Keypath from the ASX). [11]

Here’s their respective performances as listed stocks over the five years through to late 2024:

Others more immersed in EdTech have also charted the decline in value of these leading Online Program Managers (OPMs) including Richard Garrett[12] and Phil Hill.[13] They each describe the falling valuations of many EdTech/OPM stocks and the related shift some of these companies are making in prioritising more short courses to support upskilling and reskilling rather than university degrees.

In recent announcements both Keypath (through a new partnership with the Australian Financial Review)[14] and 2U[15] have launched new short course/microcredential offerings.

What went wrong with online learning and what could be done?

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit I was optimistic that student learning would not suffer as universities and VET providers moved their delivery online, except for students from rural, low SES and other disadvantaged backgrounds with less access (a) to technology, (b) less access to the ‘latest’ technology, and (c) less access to reliable internet infrastructure.[16]

Of course I realised that there would be some practical VET training which would be disrupted but having spent years listening to and learning from leading EdTech companies around the world I had seen the data and knew that, done well, online education was not just educationally sound but through the use of artificial intelligence (not GenAI, but the use of big data and sophisticated data analytics/machine learning) student learning could actually be improved when delivered online.

I shared these insights in my write-ups of different EdTech conferences I was fortunate to attend across the world.[17] [18] [19] [20][21] [22]

Of course the two most important words in the sentence above describing my optimism are “done well”.

Post-pandemic, with fewer Australian universities looking to partner with OPM specialists to take their learning online, are our universities and other tertiary education providers investing the resources needed to ensure they have the systems, processes and skilled ‘third space’ staff as well as professionally developed teachers to ensure the quality of their online learning? Or are our tertiary institutions seeing online education as merely a cheap and efficient delivery mode at a time of serious budget constraint?

Regrettably the advent of ChatGPT and other large language models from late 2022 has distracted us from this conversation in Australia.

Instead, we have been focussed narrowly (but necessarily) on the academic integrity of online learning and assessment, and with its chatbot capabilities, GenAI is now also being seen by surprising numbers of decision makers in education institutions and EdTech companies as a panacea to support online learning.

There are clearly opportunities to use large language models in course and curriculum development and in providing online tuition to students, BUT GenAI is not a short cut to high quality online education, as Prof. Rose Luckin pointed out in an address to a HolonIQ summit last year.[23]

And while tertiary institutions in Australia have been focussed so heavily on GenAI – the promise of big data and machine learning AI to truly transform education by improving student learning and reducing teacher time through data driven personalised approaches – is an educational conversation we have not realised we needed to have.

The government of Singapore recognised the benefits (after an independent evaluation of an extensive pilot of big data and machine learning to personalise learning in their school system). They have subsequently rolled out this form of AI across the whole Singapore school system.[24]

Attending last year’s meeting of the Digital Education Council in Singapore, I was not surprised to hear academics from US, European and Asian universities talk nonchalantly about personalised learning and AI in the shape of big data and machine learning. This technology is being used in their universities and is supporting students’ greater academic success.

And it is from this perspective that they are then thinking about GenAI and what it means for academic integrity, for research, for what they teach their students and for its potential use within their institutions.

There are a small number of Australian universities and private higher education institutions which are members of the Digital Education Council – perhaps they are also hearing this talk from their fellow Council members and considering how relatively modest technological changes to embrace AI that is educationally sound could make a difference to their students?

And as for the Australian VET sector – there are fewer personalised learning solutions focussed on the practical nature of VET learning but with qualification reforms allowing for the redesign of VET qualifications,[25] it may well be that we can follow the lead of the UK in particular and examine how we can also improve online learning in VET.

The way ahead

Many academics mount powerful arguments for why well designed online education can be educationally meaningful and not contribute to student loneliness and feelings of not belonging.[26] [27]

What the post-pandemic era has done is illuminated the complexities of integrating technology into tertiary education, and while EdTech solutions (in-house or with a partner) offer promising avenues for expanding access and personalisation, institutions must strike a balance between maintaining rigorous academic standards, leveraging technological innovations to enhance learning, and keep their focus on student engagement and well-being.

Well designed and delivered online learning should serve as a complement, rather than a detriment, to student academic and social development. And tertiary education institutions should be treating online learning as an important educational investment and not merely a cost-saving strategy.

————————————————

[1] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/EdTechX-Europe-2023-Summary.pdf

[2] https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/news/90-future-jobs-will-need-post-secondary-qualifications-doesnt-always-mean-uni

[3] https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/student-data/selected-higher-education-statistics-2023-student-data

[4]https://www.tcsisupport.gov.au/node/7907#:~:text=A%20classification%20of%20the%20manner,undertaking%20a%20unit%20of%20study.

[5] https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/total-vet-students-and-courses-2023

[6] https://whatnowwhatnext.buzzsprout.com

[7] https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release

[8] https://www.monash.edu/education/cypep/research/the-2024-australian-youth-barometer-understanding-young-people-in-australia-today

[9] https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/10/14/absurdity-asynchronous-courses-opinion

[10] The three companies are all Online Program managers (OPMs) ie companies that partner with educational institutions, frequently universities, to deliver online courses.

[11] Arguably the largest fall in EdTech stock in 2024 was ByJu’s but its focus was much more on school age students and afterschool tutoring and thus I am much less familiar with it, although I do have some familiarity with one of its later acquisitions, Great Learning, which has manage to navigate the ByJu’s decline successfully: https://inc42.com/features/great-learning-profitable-future-byjus/

[12] https://www.encoura.org/resources/wake-up-call/the-big-three-platforms-revisited-the-latest-on-coursera-edx-udemy/

[13] https://onedtech.philhillaa.com/p/tuesday-follow-up-20240422

[14] https://www.nineforbrands.com.au/media-release/the-financial-review-and-keypath-education-partner-launch-innovative-ai-enabled-short-course-platform-for-business-professionals/

[15] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/quick-takes/2024/12/06/2u-ends-boot-camps-shifts-microcredentials

[16] There are of course very significant issues for students in rural and remote areas and from low SES backgrounds in participating in online education. The Federal government’s study hubs are one means to helping address this disadvantage – but undoubtedly more is needed. Many Australian researchers are focussed on the digital divide, see for example: https://www.acses.edu.au/publication/covid-19-online-learning-landscapes-and-caldmr-students-opportunities-and-challenges/

https://www.acses.edu.au/publication/exploring-benefits-and-challenges-of-online-work-integrated-learning-for-equity-students/

[17] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/EdTechXEurope2022.pdf

[18] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/For-the-Future-conference-Dec-2019-1.pdf

[19] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/EdTech-in-India.pdf

[20] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/EdTechXEurope-2019-reflections-final.pdf

[21] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/China-Changing-the-Global-Education-Landscape.pdf

[22] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/EdTechXEurope-London-2018.pdf

[23] https://clairefield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Summary-HolonIQ-2024-Paris-Summit.pdf

[24] https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/files/publications/national-ai-strategy.pdf

[25] https://www.dewr.gov.au/skills-reform/vet-qualification-reform

[26] https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/banning-lecture-capture-would-not-free-students-loneliness?

[27] https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/11/08/defense-asynchronous-learning-opinion