January student visa data highlights challenges for VET

Three different international education issues have been the focus of my attention in the last week:

- the discussions at the 3rd Regional Policy Dialogue meeting of the ASEAN TVET Council (focussed on upskilling and reskilling in the face of global mega trends reshaping economies and societies)

- the 20th annual conference of the Asia-Pacific Association for International Education (APAIE) attended by 2,000 delegates in Perth this week – with a very heavy emphasis in the conference program on transnational education, and

- the latest international student visa data for Australia.

It is a pivotal time for the international education sector in Australia, and particularly VET providers.

There are real opportunities for Australian institutions to continue to make a difference to the lives and future careers of international students, but many providers are likely going to need to look more at offshore opportunities rather than a reliance solely on onshore delivery.

Firstly to the excellent recent article in The Koala News, analysing the January 2024 student visa data.

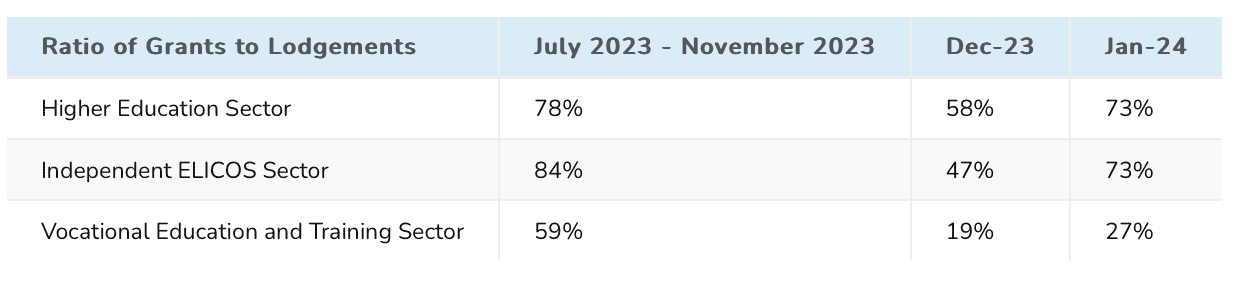

It shows that the Department of Home Affairs rejected the majority of student visa applications lodged in December 2023 immediately after the release of the Migration Strategy.

After the outcry from the sector (as the Department appeared to enact a Genuine Student test without issuing the Ministerial Direction promised in the Migration Strategy and due to take effect in early 2024 according to the Migration Strategy Action Plan) – the Department of Home Affairs reversed course in January 2024 – at least for the higher education and ELICOS sectors.

Source: The Koala News

The issue that international VET providers are faced with is this: leaving aside the opacity and unfairness of officials apparently introducing additional criteria for student visa applications before the new Genuine Student test is officially introduced – the reality is (as I have written previously) if the cost of studying a VET course in Australia will not deliver material benefits to students on their return to their home countries – they will no longer be issued with a visa for study in Australia.

And while currently onshore visa applications have higher approval rates than those from offshore, as the same test is applied to future visa applications from onshore students, they will also find it much easier to have their visa granted if they are applying for a higher education qualification rather than VET.

This is a major change to our immigration and student visa settings, and if international VET providers are to be more than either just pathways partners to the higher education sector or those offering a narrow range of courses tightly linked to skill shortages in the Australian economy – then they will need to be able to make the case, as a sector, as to why their students genuinely get a return on their investment in their VET studies in Australia.

For those who are interested in taking their VET expertise offshore – there are plenty of opportunities to do so – but new business models will need to be more sophisticated than simply taking an Australian training package qualification offshore. Instead those who succeed will be the ones who can take their skills training expertise and their understanding of industry needs and build longterm partnerships with VET providers in the ASEAN region, and in some cases directly to major employers in the region.

World Bank expert, Dr Achim D. Schmillen, speaking at the ASEAN TVET Council’s 3rd Regional Policy Dialogue identified five mega trends changing the world of work (digitisation/Industry 4.0, ageing, climate change, migration/globalisation, and COVID-19). He went on to argue that these “mega trends are not destiny, but require proactive policies” including specifically policies which strengthen reskilling and upskilling initiatives. He went on to argue that in addition to more technology and data driven approaches, we need more “modular and tailored” skills training approaches and that these need to be underpinned by a focus on enhancing institutional capacity and on fostering cooperation between stakeholders and countries.

Australia has much to offer in this regard – the question is which VET providers can and will pivot their operations to step up to help our regional neighbours to meet these challenges? And what happens to those Australian VET providers who remain focussed on the onshore international student sector as it goes through this period of significant change?

—————————————————

I will have more to say on transnational opportunities for Australian higher education and VET providers in a future update – but the standout presentation for me of Day 1 of the APAIE conference came from Prof. Lina Pelliccione, Pro-Vice Chancellor of Curtin University’s Mauritius campus.

Curtin Mauritius is, to date, the only Australian university campus in Africa and it is making a significant difference to both local and international students as well as being heavily engaged in many meaningful partnerships with businesses, government agencies and the community sector. It is an offshore campus for Australia to be proud of, and one that no doubt many in the sector will be looking at as Australia reflects on where and how to engage with Africa and its significant and growing youth population.