A tale of two regulators…

/in News/by cfa_6vgcb7

A tale of two regulators… (update 14 December 2025 re: correspondence between TEQSA and the ANU)

TEQSA

The last few weeks has seen Australia’s higher education regulator, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) flex its muscles in its compliance assessment of the Australian National University (ANU).

In an appearance before the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee inquiry into the “Quality of governance at Australian higher education providers” in late November, the CEO of TEQSA, Dr Mary Russell, was asked by Senator David Pocock whether TEQSA’s “existing remit and powers are adequate to address issues in cases where there have been gross failures of leadership or serious allegations raised against senior university leadership. Do you have the tools to be able to deal with that?”

She replied:

TEQSA provided a copy of Dr Russell’s correspondence with the ANU in answer to a question on notice (and hence while it is not available on the Senate website in the ‘tabled documents’ section – it is available in Answer to Question on Notice: SQ25-000637). There are a lot of questions and answers so to make it easier to read the correspondence – I have included the relevant letters between the ANU Chancellor and TEQSA CEO at the end of this update.

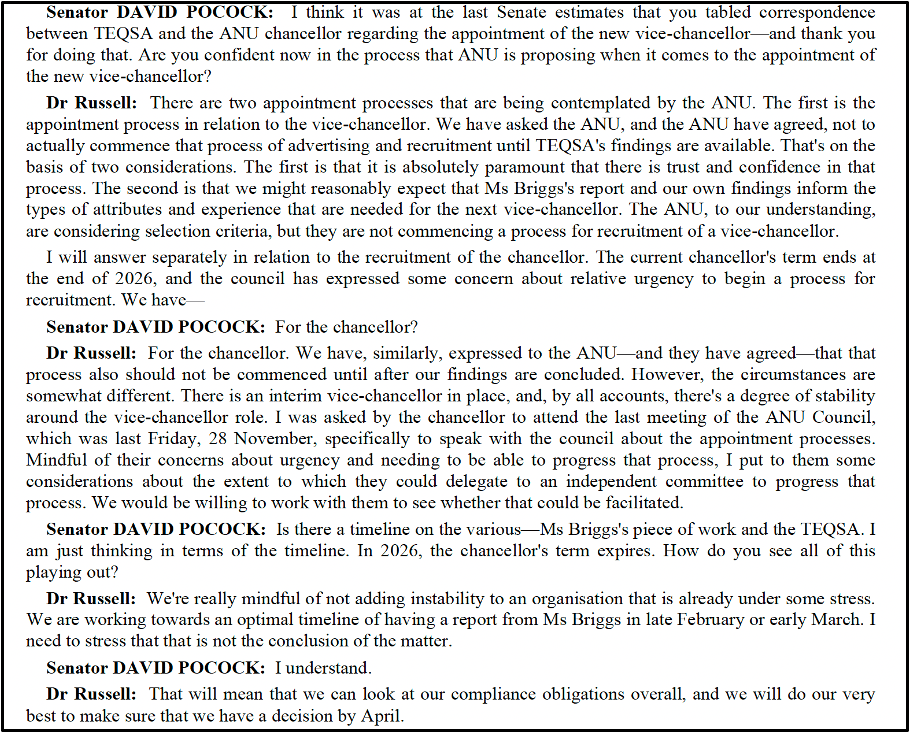

What was confirmed last week in Senate Estimates is that TEQSA has won the “stand-off” with the ANU Council: a new Vice Chancellor of the university will not be appointed until TEQSA’s work is done, and TEQSA’s work will also impact the Council’s decisions and timing in appointing a new Chancellor – potentially seeing the Council setting up an independent committee to manage the recruitment process for the next Chancellor – a process TEQSA “would be willing to work with them” on.

Here is the relevant extract in full from the 4 December Senate Estimates hearing:

Summary

The decision by the ANU Council not to proceed with recruitment of a new VC until TEQSA’s compliance assessment is concluded is appropriate.

Similarly, given TEQSA’s compliance assessment is so heavily focussed on the university’s governance, the Council should be working with TEQSA in forming an independent committee to lead the recruitment work for the new Chancellor.

Of course these are major changes to ‘business as usual’ in university governance and they may well be seen by some in the sector as interfering with university autonomy.

The reality is, as the Convenor of the University Chancellor’s Committee Prof. John Pollaers pointed out recently at the annual TEQSA conference, university autonomy historically related to academic freedom, not to freedom from appropriate organisational regulation.

The decision by the ANU Council is a sign they understand the serious potential consequences of TEQSA’s compliance assessment, and the need for a new approach to leadership at the university.

ASQA

Things have been quite different for Australia’s VET regulator, the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) which suffered a defeat in the Administrative Review Tribunal on 1 December 2025, with the decision published last week.

Worryingly, details in the ART decision point to what appear to be problems in ASQA’s decision making and potentially its conduct as a ‘model litigant’.

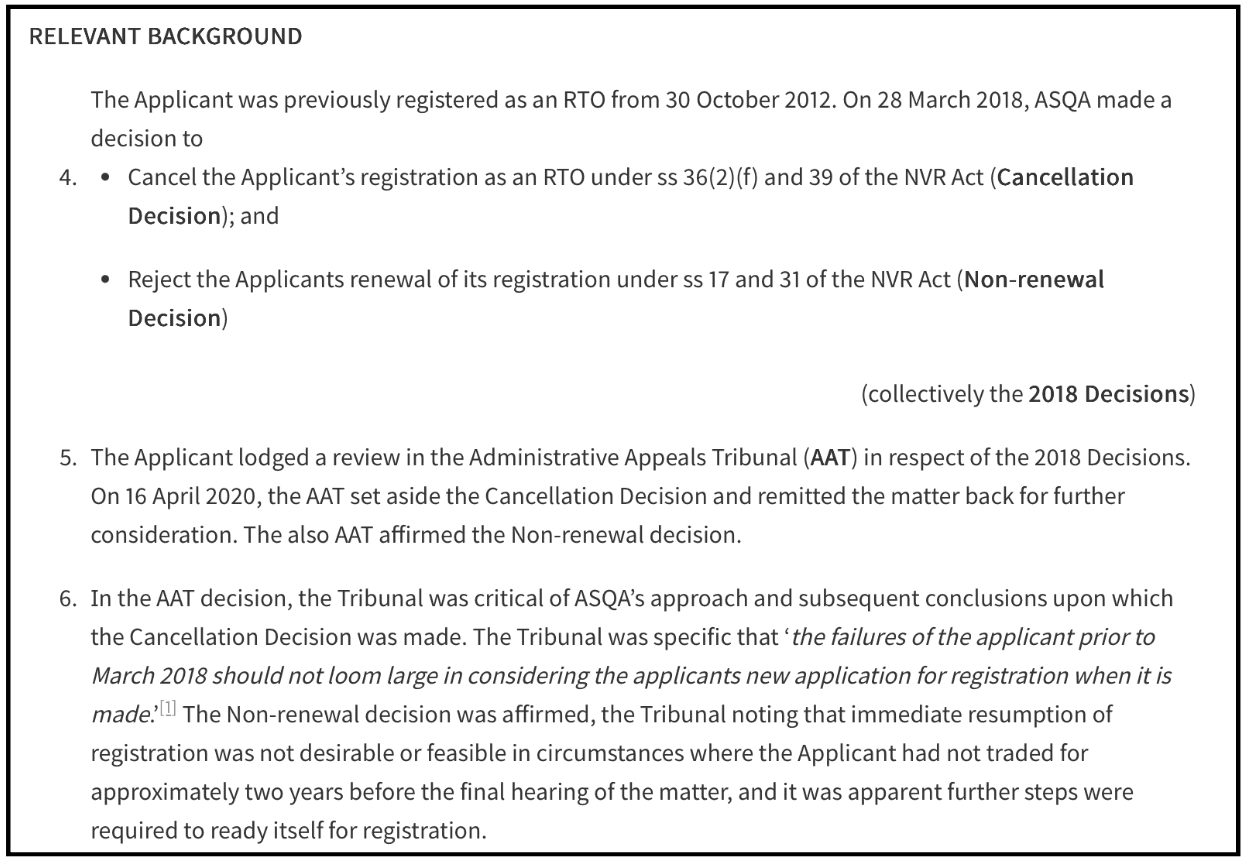

This decision relates to the case of Trades College Australia Pty Ltd (Trades College) which had its registration cancelled by ASQA in 2018, and unusually in 2024 they then lodged a new application for initial registration for the same organisation.

Here is the background to that matter, note that the Tribunal member hearing the most recent case states that “the Tribunal was critical of ASQA ‘s approach and subsequent conclusions upon which the Cancellation Decision was made” but because Trades College had not been operating for two years during the appeal process and because some of the qualifications it offered had gone through changes during the appeal process – the decision was taken that they should re-apply for initial registration rather than continuing to operate:

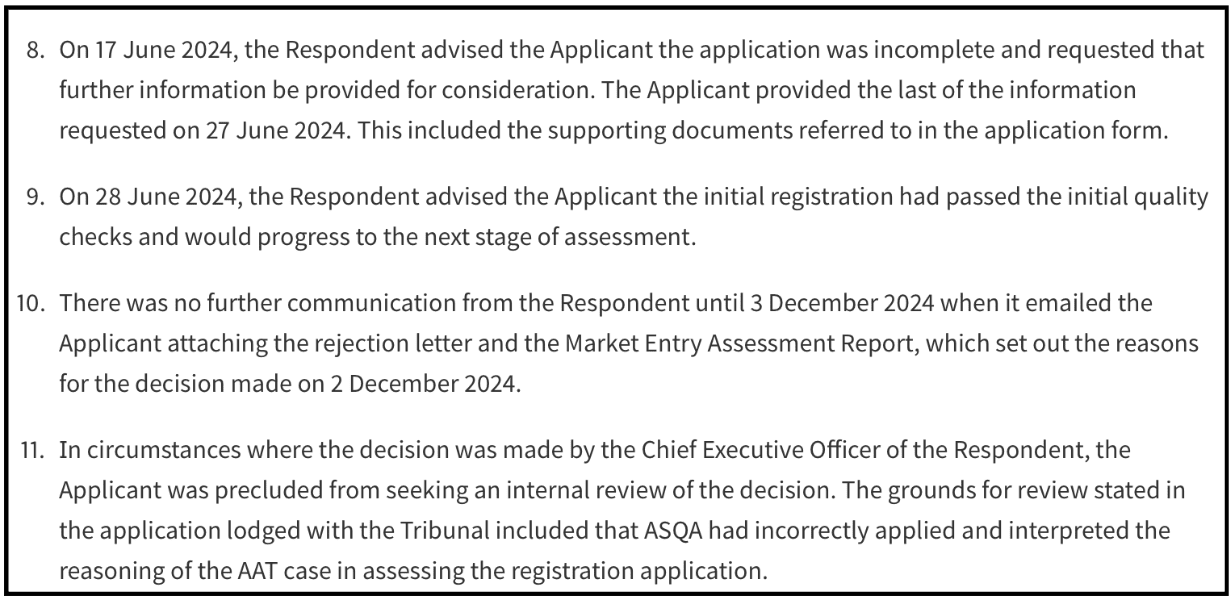

Subsequently Trades College submitted their new application, ASQA received it and said it was moving to the next stage of assessment – in June 2024. It appears that then had no contact with Trades College until December 2024 when they rejected their application and because ASQA’s CEO made the decision to reject the application, Trades College had no recourse to to seek an internal review of the rejection decision. Instead their only option was this ART appeal:

The matter then proceeded through the ART processes. Trades College provided their evidence in late June 2025. It appears ASQA chose not to lodge any further evidence/documentation. Instead they emailed the ART saying they intended to negotiate with Trades College to take the matter out of the hands of the ART and return it to ASQA for an internal review:

Perhaps unsurprisingly Trades College indicated they would prefer the matter to continue to be dealt with in the ART, so the issue the Tribunal was considering in this current case, was whether they should they agree to ASQA’s request that they should take back the decision on Trades College’s compliance and review it themselves (ie take it out of the ART):

The ART decided in favour of continuing the appeal, ie not to allow ASQA to take the decision back:

While ASQA has published media releases about their two recent wins in the ART (where the Tribunal agreed with ASQA’s decision to cancel students’ qualifications – albeit if the providers the students studied with successfully appeal the decisions to cancel their RTO registration then the students’ qualifications can be reinstated) – they do not seem to have issued media releases about this or other recent losses in the ART.

The most recent appeal by a student of an ASQA qualification cancellation decision was successful (ie the student won and has not had her qualification cancelled).

And, while it is hard to find the record on the training.gov.au website, the high profile cancellation decision ASQA took against Entry Education was also set aside (rejected) by the ART. (Go to: https://training.gov.au/organisation/details/41529/summary, scroll down to ‘Regulatory decision history’, and open either of the pdfs).

Summary

ASQA is to be supported in its endeavours to clean up the fraud and poor practice in the VET sector – but in doing so it needs to ensure that its risk assessment methods are well targeted and that its internal practices are robust and defensible.

In the interests of greater transparency it would also be good to see ASQA publish media releases about all of the decisions issued by the ART, so that the sector can better understand its successes and failures in the ART.

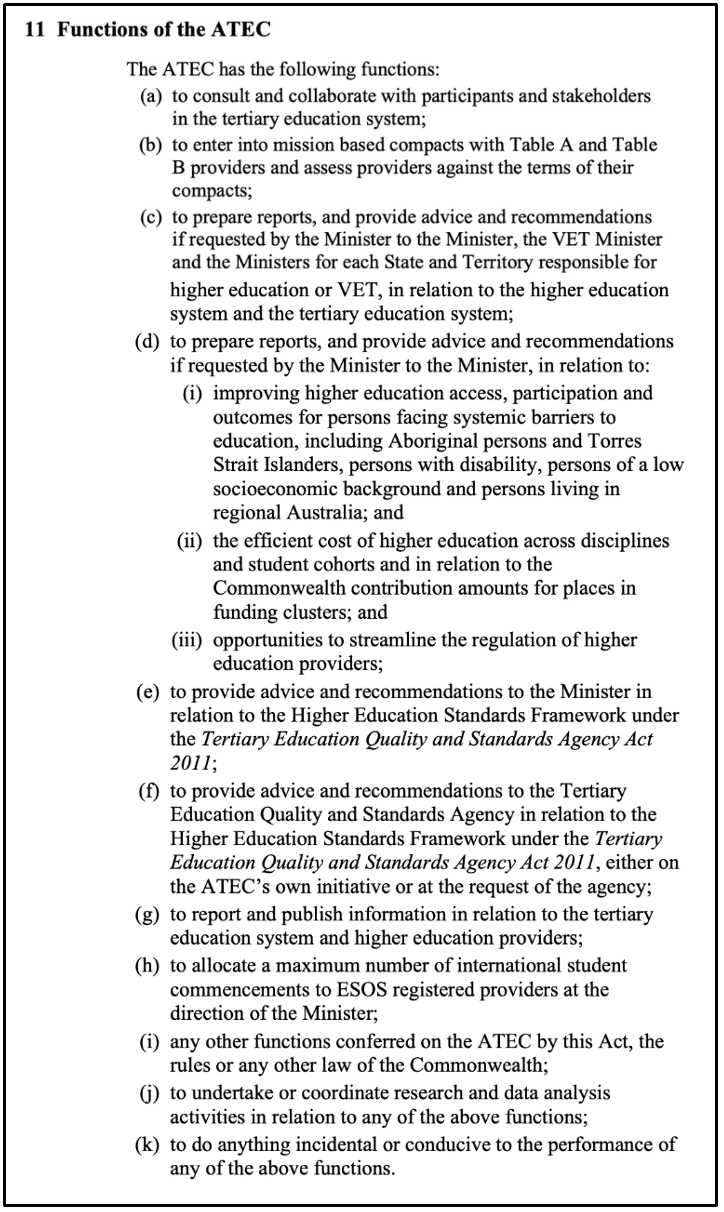

Correspondence between TEQSA and the ANU