The 2022 government-funded VET data raises questions about the relevance of some programs

As I have written previously – the advent of Generative AI has hastened the pace of change in a growing number of white collar and creative jobs. While generative AI will test the VET sector’s ability to keep its courses up-to-date and relevant – the data shows that even before ChatGPT some VET courses were becoming a lot less attractive, even where government is funding the training.

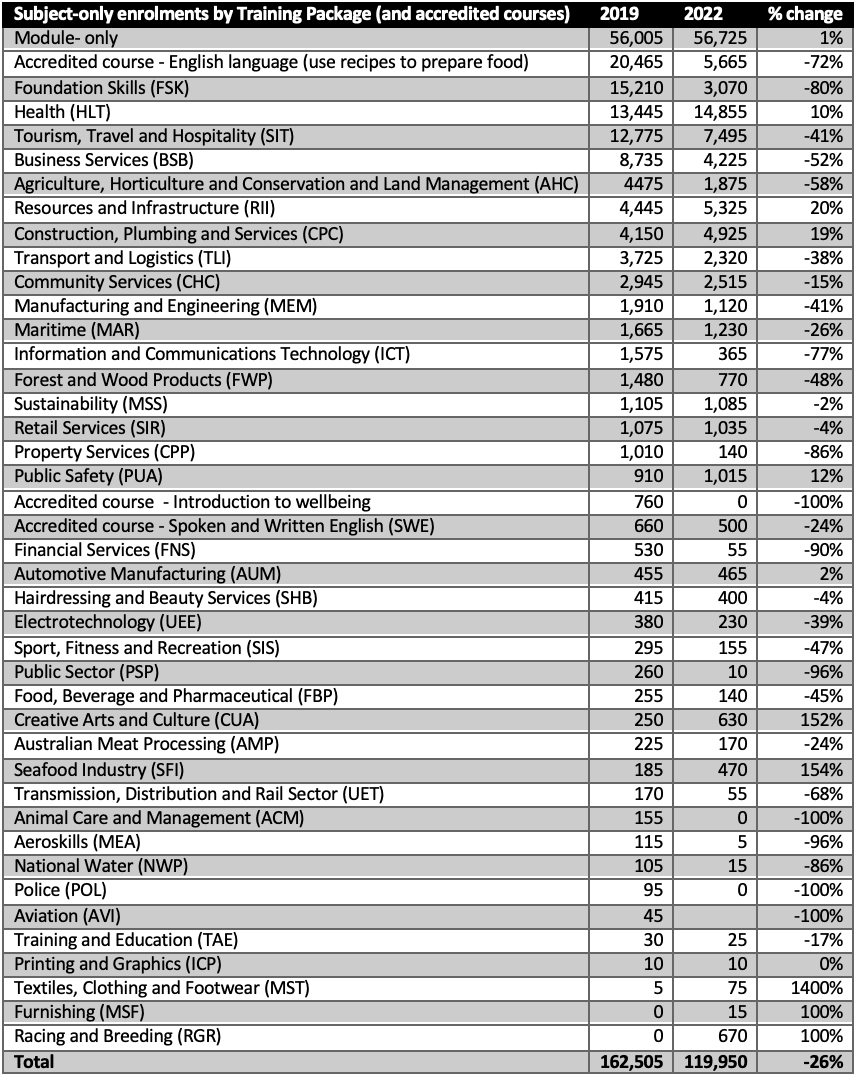

In comparing enrolments pre- and post-pandemic, the NCVER’s latest data shows that VET’s government-funded ‘microcredentials’ (ie subject-only enrolments) are much less popular than they were. At a time when in other sectors and countries there is an increasing use of short courses for upskilling and reskilling – it is worth considering what this means for the Australian VET sector?

Note in the following table (a) the enduring number of enrolments in ‘modules’ which are usually associated with accredited courses developed in response to emerging industry needs (and hence have not gone through the Training Package development process) and (b) the decline in enrolments/government funding for English language and Foundation Skills short courses.

And then note also the relative decline in government-funded enrolments in most other popular Training Packages.

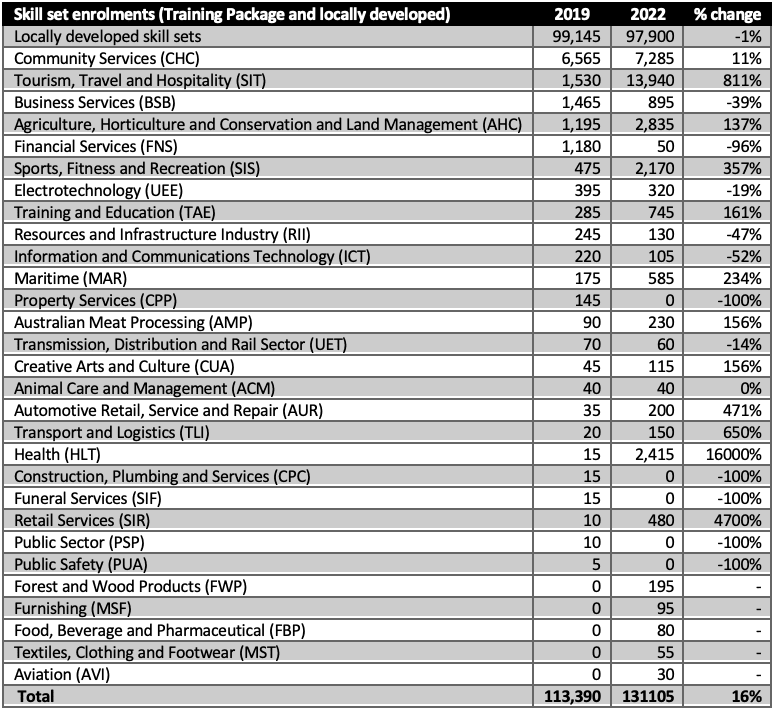

Government-funded enrolments in Skill Sets (specially developed short courses comprising more than one subject, unit or module) have increased modestly since 2019 – but once again the relevance of what is being offered in many Training Packages must be questioned when 75% of enrolments in government-funded skills sets in 2022 were in “locally developed” skill sets (ie educators selecting groups of subjects to package up for learners instead of using those developed through the Training Package process).

Another NCVER dataset raises further questions as to the relevance of Australian VET courses. The data on enrolments in offshore VET shows that providers have struggled to find a market for VET qualifications: in 2019 there were only 26,000 offshore VET students compared to more than 120,000 offshore higher education students.[1]

Half of all offshore VET students were in China (13,245) with another 975 in Hong Kong – which suggests that outside of the Chinese VET system there is little interest in Australian VET qualifications.

These were points I raised in recent evidence to the Joint Standing Committee’s Inquiry into Australia’s tourism and international education sectors. Instead of delivering VET qualifications offshore, it appears anecdotally that Australian VET providers are instead moving to deliver non-accredited training, industry-certified training, and/or local VET qualifications from the countries they are operating in offshore.

With the new Jobs and Skills Councils now in place, it is time for the VET sector to start thinking about new tripartite approaches to gathering intelligence on industry’s changing skill needs. And then to start working with VET providers to enable more timely updates to VET qualifications and units of competency.

If this cannot be achieved it looks likely that the drift away from VET will continue, especially with the changes generative AI is bringing to white-collar work, software engineering and coding, and the creative arts.

As La Trobe University’s Vice Chancellor, Theo Farrell, cautioned recently – AI will be as transformative as the industrial revolution but at a much faster pace. “… it’s going to displace a lot of activities and jobs. If we don’t do it right, we risk increasing inequality in our society.”

————————

[1] https://internationaleducation.gov.au/research/offshoreeducationdata/Pages/Transnational-Education-Data.aspx